This blog post was kindly provided by Chris Hawksworth from Kilwinning Heritage. Check out their website to plan your visit to the Heritage Centre at Kilwinning Abbey Tower. Or why not give them a follow on their Facebook page?

John Campbell Brisbane, a gentleman of independant means, died in July 1868. He had inherited the estate of Lylestone from his father, Thomas Brisbane. In his will, John, who had no family of his own, gifted Lylestone to Hugh King, solicitor and bank agent in Kilwinning. Hugh King had acted as factor at Lylestone on behalf of Brisbane. The estate consisted of the farms of High Gooseloan, Lylestone, and High Monkredding, although the fields of High Monkredding were usually divided between the other two farms when they were let to tenant farmers. In the 1860s, both the enlarged farms had limestone quarries from which the tenants could extract limestone, but only for use on their own farms. In the 1880s, Hugh King disponed the Lylestone estate, including the mineral rights, to his sons Hugh Brisbane King and Robert Craig King, both of whom were also solicitors in the family firm. By the time of Hugh King’s death in 1891, the brothers had taken over the running of the Lylestone Quarry Company.

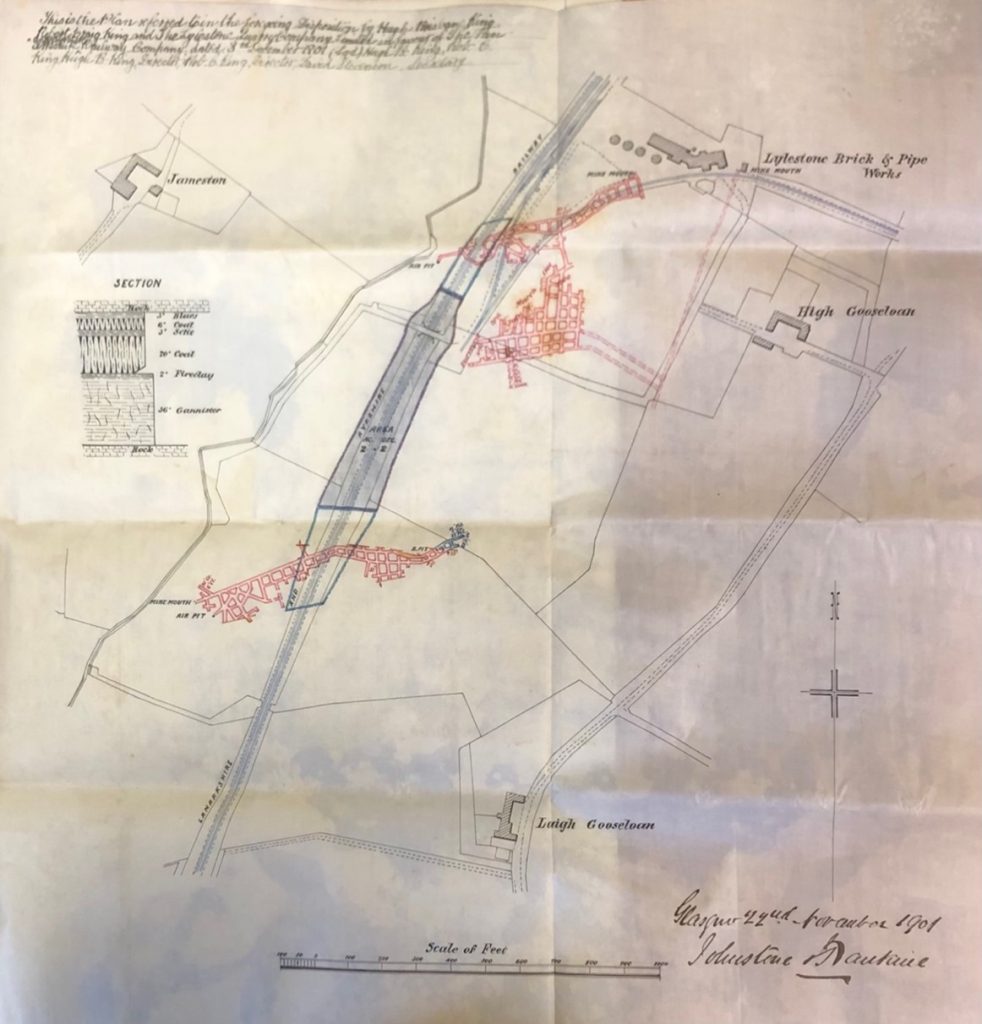

The 1856 OS map shows a small limestone quarry at High Gooseloan, a larger limestone quarry adjacent to High Monkredding farm steading, and a smaller freestone quarry to the north of the steading. By 1897 when the next OS maps were published, there had been significant changes on the estate. The freestone quarry had been enlarged and renamed Lylestone Quarry. A mineral railway had been built linking the quarry to the Lanarkshire & Ayrshire Railway near High Gooseloan, and Lylestone Brick & Pipeworks had been built at High Gooseloan too. A short narrow gauge tramway crossed the L&A railway, linking the sidings at High Gooseloan with two small quarries on the otherside of the railway. Documents in the Frew Collection and various newspaper articles throw some light on how these changes came about.

In September 1888, the Lanarkshire & Ayrshire Railway opened its line between Kilwinning and Barrmill. The Lylestone Quarry Company saw the railway as an opportunity to enhance its business. Thus in November 1889, tenders were sought to construct a branch railway from High Gooseloan to the quarry, a distance of 3/4 of a mile. The lowest bid was £775/8/5 from Hugh Symington & Sons of Coatbridge. These contractors had also been asked by the L&A Railway to bid for their sidings at High Gooseloan where goods from Lylestone would be transhipped. That same month, the quarry company also advertised in the Glasgow Herald for a ‘locomotive of any make able to draw 20 tons gross up a 1 in 40 gradient’.

Again in November 1890, the Glasgow Herald carried adverts from the Lylestone Quarry Co for a ‘Traveller in Freestone and Bricks’, to be based in Glasgow (a traveller was a travelling salesman). A similar advert had appeared in the Belfast Newsletter earlier in the year for a traveller around Belfast & neighbourhood. This implies that as well as quarrying stone, the company was also producing bricks and hoped to do business outwith the west of Scotland.

Construction of the brick and pipeworks began in early 1890, to plans produced by John Armour, Jnr, an Irvine architect. James Robertson, Kiln and Furnace Builders of 20 Armadale Street, Glasgow, supplied a 20 foot diameter kiln capable of holding 2000 3″ bricks at a time. William Greig had his estimate for digger work, brick and masonry work accepted. This included engine, mill and boiler houses to be built with brick walls, gables and floors, and stone window sills and lintels. The boiler was supplied by William Wilson & Co of Lilybank Boiler Works, Glasgow.

The brickworks would have required maintenance and structural improvements over the ensuing years. In 1892, there was an agreement with John Stewart & Son, Founders, Irvine Iron Works to produce new iron ‘wet pans’ for the fireclay works. An advert for contactors to build a drying shed at the fireclay works appeared in the Ardrossan & Saltcoats Herald in January 1894.

1894 seems to have been a busy year for the Lylestone Quarry Company. Doubtless in an effort to raise more finance, the firm became a Joint Stock Company with a capital of £5000 in £1 shares. Hugh Brisbane King and Robert Craig King each took £1000 worth of shares in the new Lylestone Quarry Company Limited. At the time the Joint Stock Company was formed, its assets were listed as follows:

Quarry

Working faces £400

Machinery & tools £701

Brick & Pipework

Buildings £1703

Machinery £1704

Mine

Pits etc £531

Machinery etc £240

Railway £1437

Lime Work

Kiln & Road £127

General machinery

inc pony, furnishings £153

Total stock of goods £522

Overall value £7518

Clay for the brickworks and coal to fire the kilns were probably worked locally. The quarry would have provided some of the clay, the rest would have been worked in the coal mines. There were two coal mines at High Gooseloan as evidenced by the plans of minerals under the railway which were sold to the railway company on different occasions. The mines were probably drift mines as there is no sign of pit head buildings on any of the plans or OS maps.

Conditions in the mines were not very safe. In June 1892, John Ronaldson, HM Inspector of Mines, informed the King brothers of several infringements of the Coal Mines Regulation Act at Lylestone mine. Amongst other lesser faults, the communication between the mine mouth and the escape shaft was not of the prescribed height. It also transpired that for the previous 3 years there had been no second outlet from the pit, i.e. no escape shaft. The inadequate exit that was in place had only been opened up a few days before the inspectors visit. He insisted that the mine should cease normal working until the escape exit had been enlarged to the recommended level. During the 1894 national miners strike, the Lylestone mine was kept going by 3 or 4 men until a visit by a group of pickets persuaded them to down tools on July 12th.

In 1896, the Lylestone company added some new grinding machinery to their brickworks enabling them to produce Ganister bricks. Ganister was a mixture of ground silica quartz and fireclay which was used for lining furnaces in forges and iron foundries. Adverts for Lylestone Ganister were regularly placed in newspapers across the UK until 1903.

Despite the 1910 OS map showing further expansion of the quarry face, the tramway over the L&A railway was no longer present. The business must have been in difficulties as it was formally dissolved in 1914. The previous October, an advert had appeared in The Scotsman for an auction of quarry and brickwork plant, steam and hand cranes, and the branch railway, at Lylestone Quarry. The equipment listed included a 7 ton derrick crane by Morgan of Kilwinning. There were also various tile and pipe making machines, steam boilers, stone cutting saws and winches. Railway equipment included nearly a mile of standard gauge railway track and some stone wagons, as well as tram rails and steel side tipping wagons of 3′ gauge. These 3′ gauge wagons presumably ran on the tramway rails, possibly on the tramway over the L&A line or potentially in the coal mine.

At the time of closure, the quarry manager was William Douglas, who had held that position for at least 20 years. In 1914, he formed the Douglas Fireclay Company at High Monkcastle (between Kilwinning and Dalry). According to the Valuation Rolls, Lylestone brickwork was let to the Douglas Fireclay Company until 1918/19 when the works and associated coal mine were recorded as ‘unlet’. Five years later the Valuation Rolls recorded the works as ‘ruinous’. Today, the brickworks site is overgrown with trees. The line of the branch railway to the quarry forms the boundary of a forestry plantation which surrounds the flooded quarry remains. Occasionally, Lylestone bricks can be found, but the most accessible reminder of the quarry is the former Cooperative building in Main Street, Kilwinning, which was faced with stone from Lylestone in 1894.